The Elephants That Walked East: From Hamburg to the Empire of the Rising Sun

If there is a zoo in Taiwan that has truly captured the public imagination in recent years, it is undoubtedly Hsinchu Zoo. In 2017, its gates quietly closed, leaving many to wonder what would emerge after the renovations. By late 2019, the zoo reopened—freshly reimagined, reborn, and vibrant with newfound purpose.

Modern gate of Hsinchu Zoo.

Today, Hsinchu Zoo is praised for its stylish, contemporary appeal. Yet, beneath its modern surface lies a history stretching nearly ninety years into the past, to Taiwan’s era under Japanese colonial rule. Visitors familiar with larger zoological parks often pause at the entrance, puzzled by how such a compact, two-hectare zoo, with two distinct gates, one historic and one modern.

The historic gate of Hsinchu Zoo.

The story begins at the older entrance, guarded by two solemn, cast-iron statues—an elephant and a lion locked in eternal stillness. They stand framed by neoclassical pillars and delicate ornaments, blending European romance with colonial ambition. Modest in size, the gate nonetheless commands quiet authority. Designed in 1936 by Japanese architect Shige Morita (森田重), it has remained intact for decades and is now officially recognized as a historic structure. During the 2017 renovations, workers painstakingly scraped away thirteen layers of paint, eventually uncovering its original shade: a serene blue-gray, resonating deeply with the zoo’s colonial past.

This gate, known affectionately today as the "Elephant Gate," did not originate in Taiwan or Japan. Instead, it took direct inspiration from Hamburg's famed Tierpark Hagenbeck—a zoo that once reshaped how people around the world imagined zoological gardens.

Hagenbeck’s design traveled far beyond Europe, catching the attention of the Japanese Empire during its first wave of imperial expansion. In 1895, following its victory in the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan annexed Taiwan—its first overseas colony and its first real step into imperial power. Japanese architects and intellectuals eagerly embraced Western models of modernity—including the very concept of a zoo, which was translated directly into the Japanese-coined word "dōbutsuen" (動物園), now commonly used across East Asia.

But what made Hagenbeck Zoo so extraordinary? Why did its vision captivate Japanese architects and lead them all the way to Taiwan?

Historic photo of the gate of Hsinchu Zoo. (Source: 新竹州要覽)

Rising Sun Flag of Japan. (Source:Wikimedia)

Backyard of the Future: How the Hagenbecks Reimagined the Zoo

The legend begins in 1848, along the frigid northern banks of Germany’s Elbe River. Fishermen pulling in their nets shouted excitedly, “We've caught six seals!” Quickly returning to Hamburg, they reported their unusual catch to Gottfried Hagenbeck, Carl’s father, who was once a fishmonger. He placed the seals into two large wooden basins in Hamburg’s busy Spielbudenplatz. By evening, a curious crowd had gathered, each paying a penny to glimpse the seals.

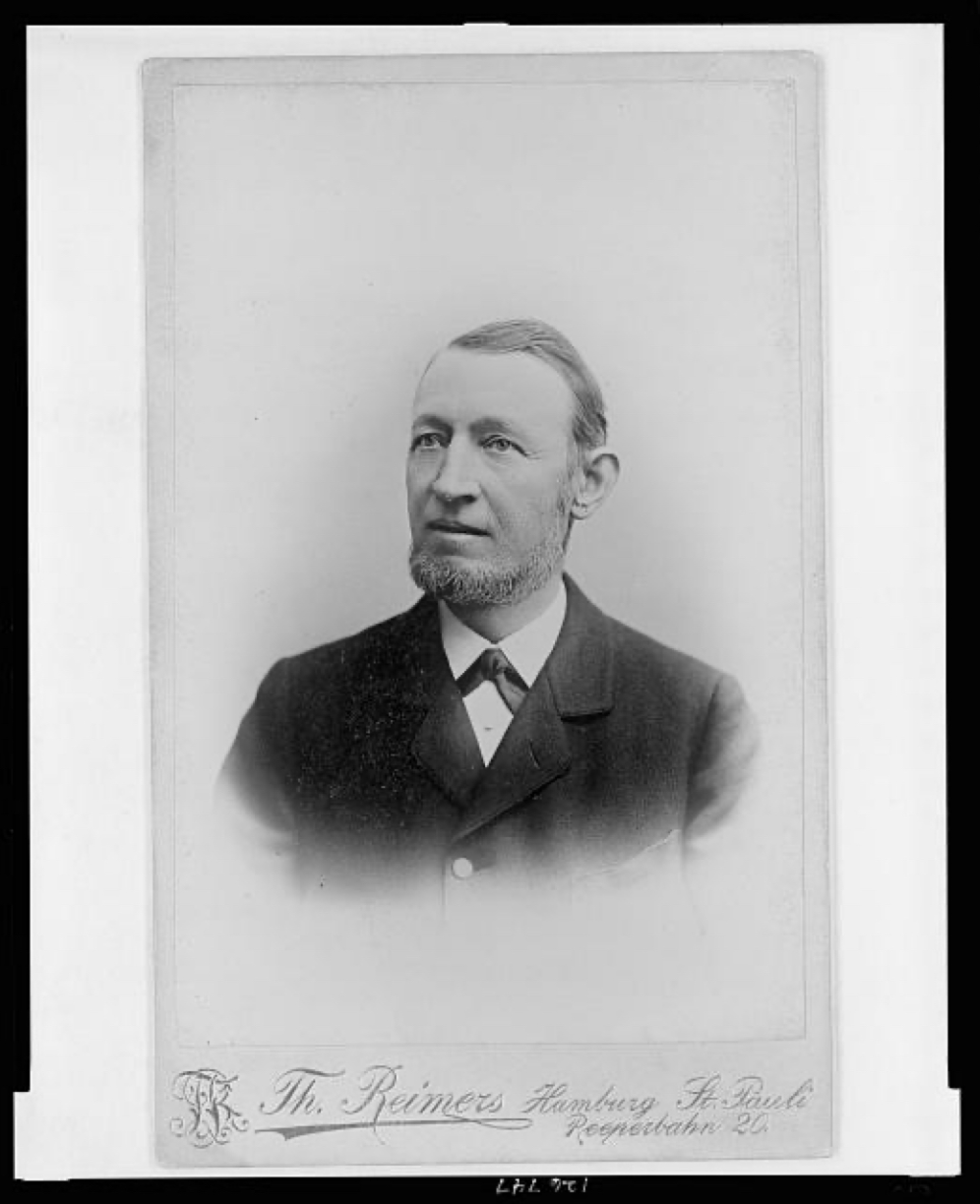

At the time, Carl Hagenbeck was just four years old—far too young to realize that this impulsive decision would not only bring sudden wealth, but also spark a lifelong bond with animals, one that would forever tie his family to the world of wildlife.

Carl Hagenbeck. (Source: Library of Congress)

That first encounter with the seals left a lasting impression on the Hagenbecks. They came to realize that animals from “foreign lands” were not just exotic curiosities—they were a lucrative business opportunity. So the family pivoted decisively: from fishmongers to wildlife traders. Within just two decades, under the family’s relentless efforts, the Hagenbecks had become the world’s largest dealers of wild animals. They employed professional hunters and contracted local Indigenous communities to source animals across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, supplying zoos and circuses throughout Europe and North America. In an era when Germany had yet to acquire overseas colonies, it was an astonishing feat to build such an expansive global trade network.

By 1874, Carl Hagenbeck—now an adult—converted a vacant lot and stable behind his family home into their first private zoo. There, he exhibited majestic animals—hippos, zebras, antelopes, and other strange and marvelous creatures. The zoo also featured so-called “ethnographic displays,” where foreign Indigenous people were presented alongside the animals, turning the site into a spectacle that drew throngs of curious Hamburgers eager for a glimpse of the distant and unfamiliar.

But over time, Carl Hagenbeck grew increasingly restless. His menagerie was rare and impressive, yes—but something about it felt wrong. Something was missing. In his memoir, he confessed:

“I longed to give the animals more space. I truly didn’t want to see them crammed into cages—I wanted to see them roam, slowly and freely, in open landscapes.”

To Hagenbeck, watching animals pace back and forth in cramped enclosures felt little different from observing taxidermy specimens in a museum. “I want to show animals as they truly are in nature, through a new lens of freedom,” he wrote. He began to envision a different kind of zoo—not one built with bars and fences, but one that created the illusion of boundless wilderness. A “wild,” “natural” zoo, where animals could move slowly through open landscapes designed to resemble their native habitats as closely as possible.

It was a radical idea, ahead of its time. The world, still bound by cages and convention, had not yet caught up.

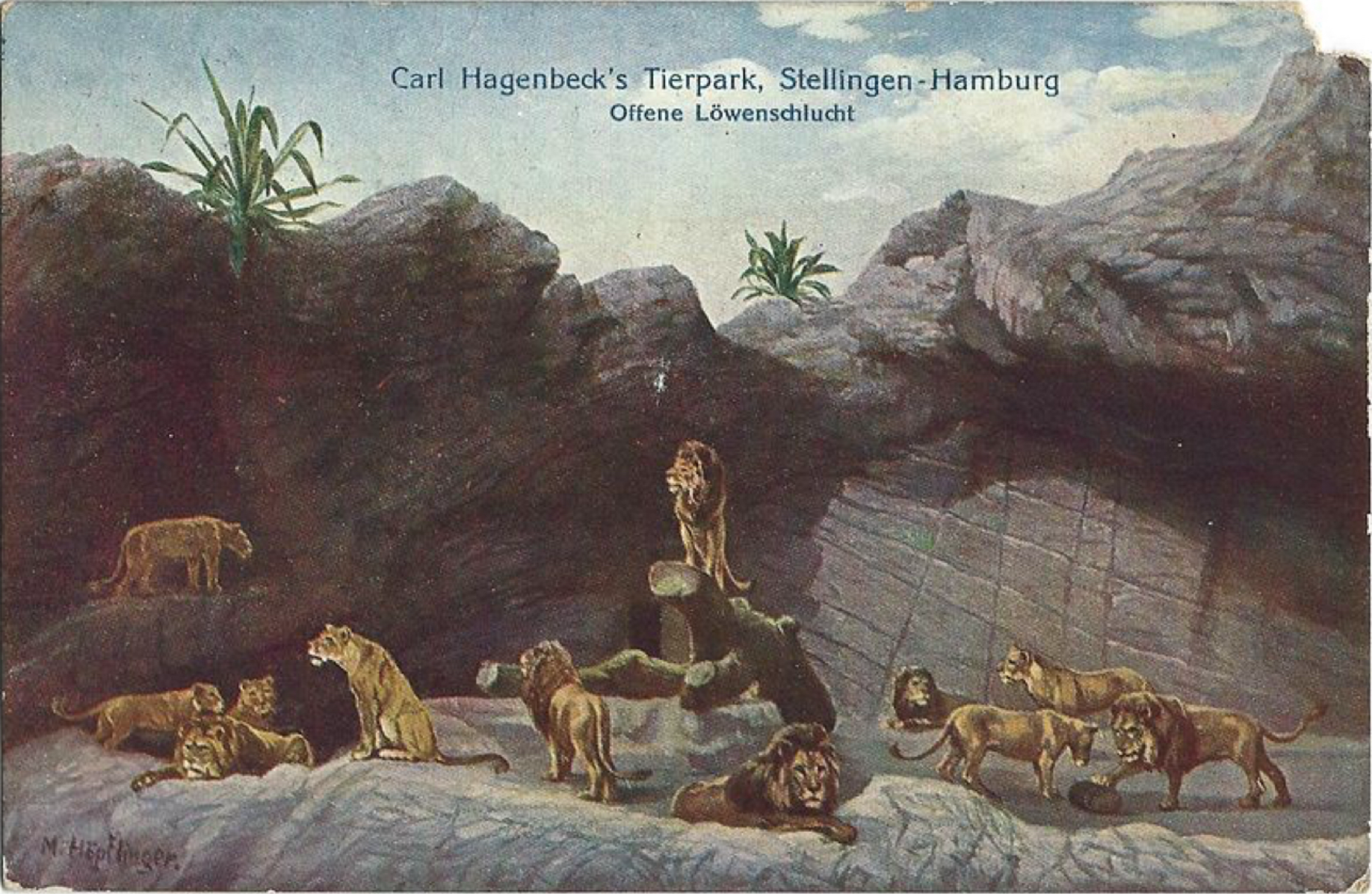

But in the hilly outskirts of Hamburg, in the district of Stellingen, Carl Hagenbeck quietly began to reshape the future. On a plot of land just beyond the city, he brought in Swiss sculptor Urs Eggenschwyler, who had previously worked for the Hagenbecks. Eggenschwyler was among the few at the time experimenting with moats instead of cages—sunken barriers that allowed predators like lions to appear untethered, roaming freely in open spaces. Hagenbeck believed a moat could surely replace the cage: animals would appear free, while still remaining safely contained.

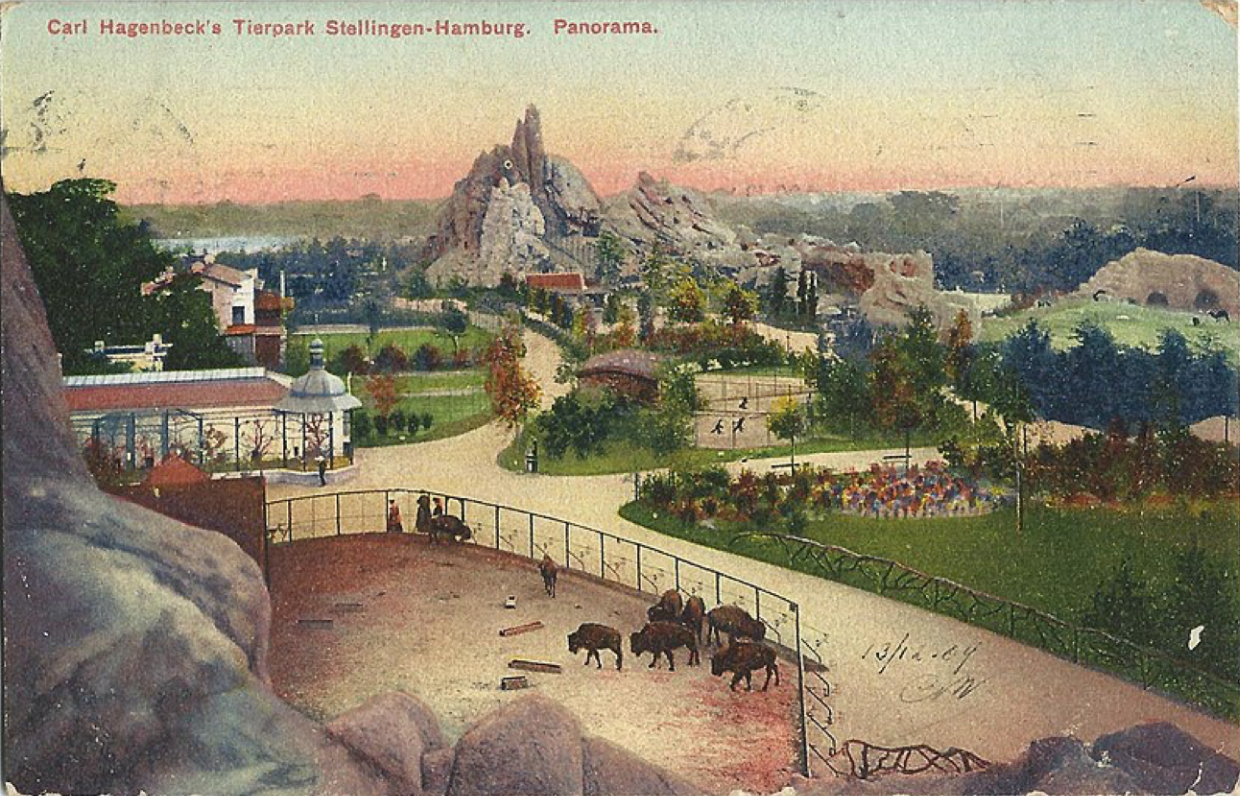

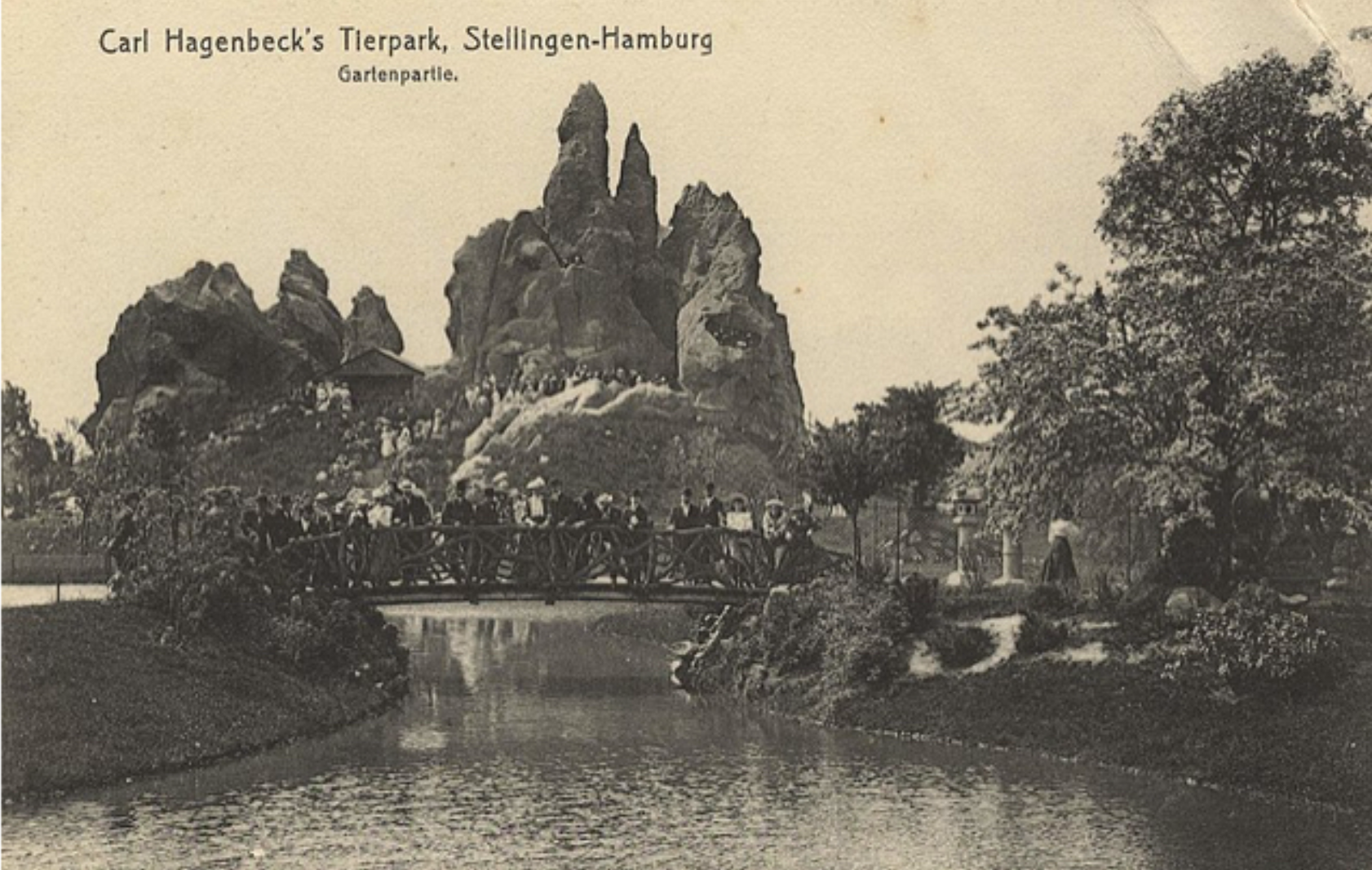

On May 7, 1907, Carl Hagenbeck’s second zoo—Tierpark Hagenbeck—opened its gates to the public. It was more than a zoo; it was a revolution. A new kind of zoological park was born, one that abandoned iron bars in favor of illusion, landscape, and motion. And from that moment forward, its influence would ripple outward—across London, through Tokyo, and eventually, deep into the heart of the Empire of Japan.

1909 Postcard of Tierpark Hagenbeck. (Source: Wikipedia / public domain)

When the Bars Fell: Tierpark Hagenbeck and the Architecture of Illusion

It was a Tuesday when the gates finally opened, and the quiet of Stellingen was broken by the rumble of crowds. The newly laid light rail line trembled under the weight of eager passengers pouring into the sleepy town. A revolution—quietly staged, but widely anticipated—was underway.

Visitors and journalists streamed toward the grand entrance—the very gate that would later inspire the design of Hsinchu Zoo. At its center stood a striking sculptural tableau by the young, animal-loving sculptor Josef Pallenberg. Atop the twin columns flanking the archway, two sets of animals held dramatic poses: on one side, polar bears of the Arctic; on the other, lions of the African savanna. The entire composition glowed under cleverly concealed lanterns. The archway proclaimed, in no uncertain terms, the promise of this new kind of zoo:

“One ticket, and you can travel the world.”

The animals themselves were symbols. Together, the polar bears and lions captured the essence of Hagenbeck’s sweeping vision—what he would call his “Arctic Panorama” and “ African Panorama”. The world’s extremes, now made walkable, visible, and accessible—for the price of admission.

The “original elephant gate”. (Source: An-d / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Excited visitors passed through the grand gate and entered a landscape that felt more like a romantic painting than a zoological park. Guided by signs and flanked by rustling foliage, they strolled down a tree-lined path toward the central plaza. Smoke and steam drifted from bustling restaurants, where the scent of sausages and beer filled the air. Benches lined the neatly arranged rows of trees, inviting rest, but few paused for long.

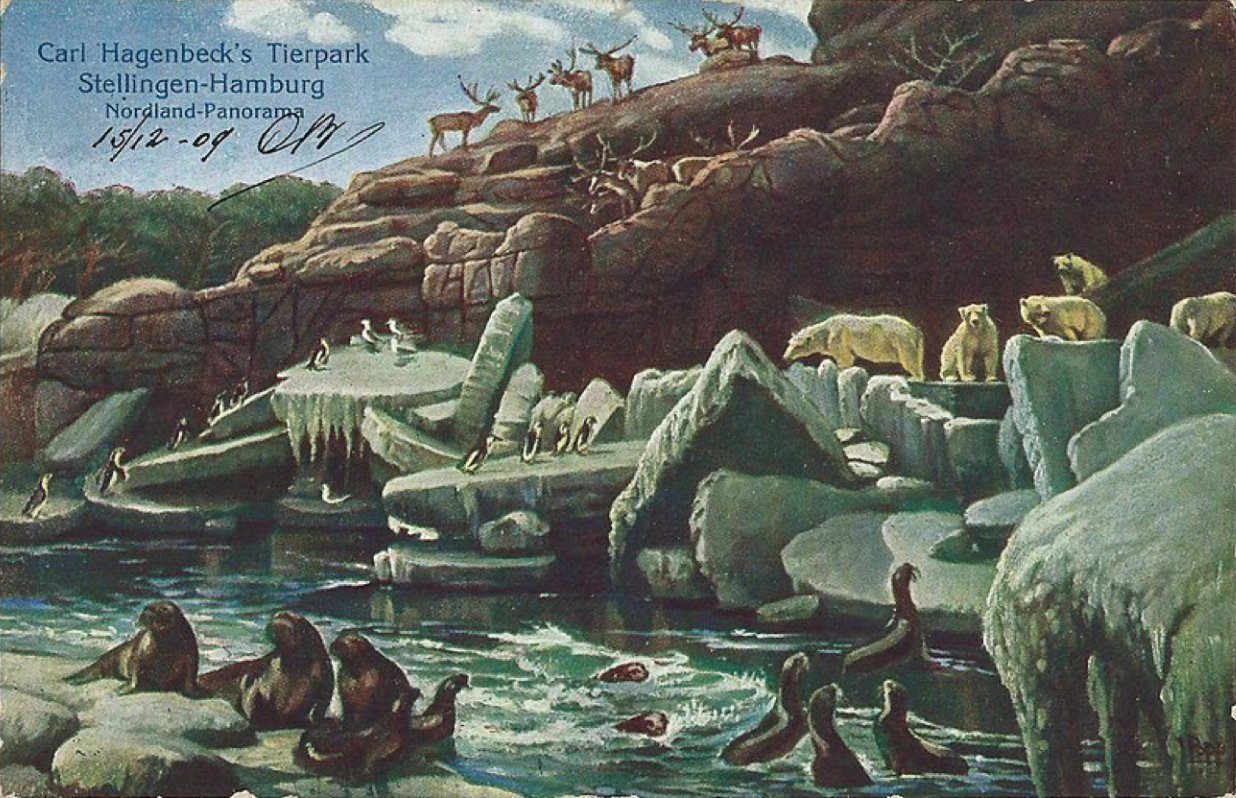

At the heart of the plaza, guests found themselves face to face with two dramatic worlds: to the left, the Arctic Panorama, crowned with snow-white peaks; to the right, the African Panorama, where lush trees and towering palms framed a shimmering lake. Between them lay a surreal landscape of rocky cliffs and grassy slopes—a theatrical composition so sweeping it left visitors in stunned awe.

In the polar zone, waist-high railings separated guests from a valley of rising ice. Closest to view were sea lions and walruses—some basking on sun-warmed rocks, others plunging into icy pools. Further back, massive fissures cracked through an artificial glacier, releasing house-sized chunks of ice in staged avalanches. Polar bears paced among the rubble, dwarfed by their man-made kingdom of sculpted snow and fiberglass icebergs. At the highest point, a pair of reindeer stood solemnly on a cliff ledge, their silhouettes outlined against a frozen wall, gazing into the distance.

There were no cages here. Not a single bar obstructed the view. Instead, Eggenschwyler’s illusionary cliffs—modeled after the Alps and crafted from layered concrete—served as the backdrop for one of the most extraordinary spatial tricks in zoo history. By manipulating elevation, terrain, and animal behavior, he conjured invisible barriers: a seal wouldn’t dare cross the flat terrain where polar bears prowled; a reindeer would never leap from a sheer cliff face.

Postcard of “Arctic Panorama”. (Source: Wikipedia / Public Domain)

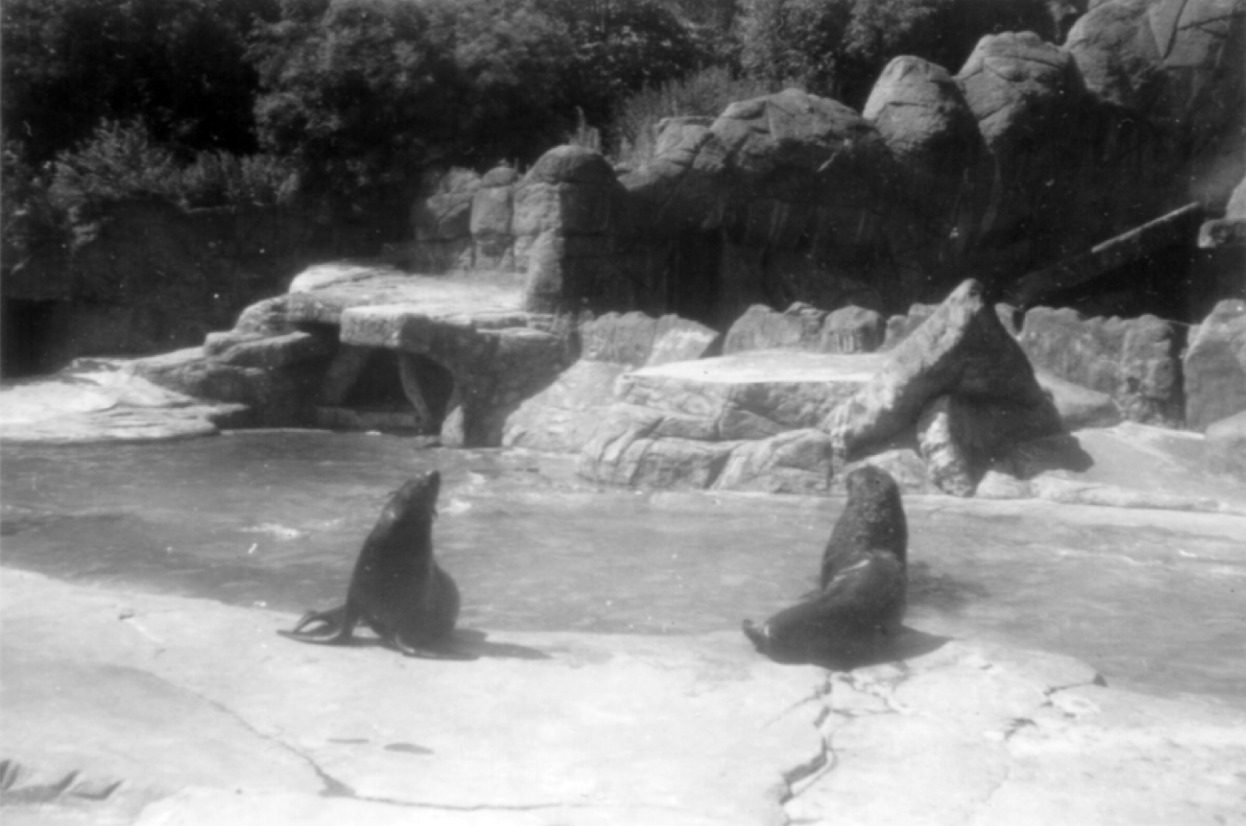

Sealions in “Arctic Panorama”. (Source: Reise Reise’s grandfather / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Then came the tropics—an expansive, immersive landscape composed of four seamlessly integrated zones. Along gently sloping paths, visitors wandered among animals native to the African grasslands, weaving through open plains dotted with ponds, rolling hills, and rising escarpments. Each zone sat slightly higher than the last, creating a terraced illusion that made it feel as though one were walking deeper and deeper into the wild.

The first tier featured a broad wetland, where flamingos waded among cranes and other waterfowl. On the second level, ostriches and zebras dashed across grassy fields shaded by towering trees, while bighorn sheep grazed in the dappled light. The third zone revealed a crowd favorite: a lion valley, sunken deep into the hillside. And at the highest tier stood a jagged artificial cliff, where mountain goats bounded from ledge to ledge with breathtaking ease.

There were no fences. No bars. Only landscape.

For many first-time visitors, the moment they saw a lion—unobstructed, framed only by earth and sky—something shifted. There was awe, certainly. But also a quiet, unexpected emotion: reverence, wonder, perhaps even disbelief. For the first time, people could truly gaze upon a lion—whole, alive, and uncaged.

Postcard of “African Panorama”. (Source: Wikipedia / public domain)

Postcard of “African Panorama”. (Source: Zeno.org / public domain)

The Arctic Panorama and the African Panorama were met with extraordinary success, offering a cinematic, almost painterly experience unlike anything the public had seen before. Within these wild, immersive habitats, predators and prey were placed within the same visual frame—a deliberate compositional choice that evoked both harmony and tension, satisfying a deep human longing for nature as it ought to be.

In other words, Tierpark Hagenbeck offered more than a menagerie. It gave visitors a living landscape—a sweeping tableau in which every view felt composed, curated, almost staged.

“I want to display live animals in nature, from the best possible angle.”

That was Carl Hagenbeck’s dream. And at last, it had taken shape—inside the frame of a living painting.

Geography vs. Taxonomy:

Fuse of the Great Zoo Debate

For the first time, a zoological park was built not merely of iron and concrete, but of intention—an intention to change how people saw animals. Heini Hediger, later hailed as the father of zoo biology, called the Hagenbeck model “a philosophical innovation before it was a structural one.” It turned the zoo from a cabinet of curiosities into an encounter with the living world.

Until then, zoos had existed to satisfy basic wonder. A lion, a bear, an elephant—no different from museum specimens that happened to blink and pace. Hagenbeck changed that. Visitors now saw bodies in motion, animals set in landscapes that mimicked their homelands. The zoo became a stage; the animals, its actors—ambassadors of the wild whose every movement performed “nature” for a watching public. Civilization met wilderness here, and expectations were forever altered.

Not everyone applauded. Though crowds were dazzled and reporters effusive, many experts bristled. With his Arctic and African Panoramas, Hagenbeck built the first zoo organized by geography. Taxonomy—the old logic of “Monkey House,” “Feline Pavilion,” “Aquarium”—was brushed aside. For Hagenbeck, classification was a human abstraction; geography was how life actually breathed.

Ludwig Heck, the formidable director of the Berlin Zoo, sneered: “What is this nonsense? Mixing animals just because they share a map? It’s nothing but rocks and beasts to please the crowds.” His disdain echoed through academia, where Hagenbeck’s dreamscape was dismissed as shallow, unscientific—vulgar, even.

The feud spilled into public debates among Germany’s leading zoo directors. Across the Atlantic, American colleagues watched with wary fascination. William Temple Hornaday of the Bronx Zoo quipped, “That damned zoo of Hagenbeck’s—it doesn’t teach you a thing, but it sure keeps people from leaving early.”

Echoes Across Empires: How a German Dream Reached Taiwan

Critics grumbled, but the truth was undeniable: the visitor experience at Hagenbeck’s zoo was wildly successful. And like any good idea, it spread—first across Germany, then outward to London, Paris, Vienna, and eventually even to the Bronx and Buenos Aires. Each city seemed eager to dig its own moats and raise its own concrete hills, chasing the illusion of a freer, more heroic wilderness.

This wave of influence reached East Asia not through cultural admiration but through empire. As Japan rose to imperial power in the early 20th century, it embraced Western notions of modernity, including Hagenbeck’s radical vision of the zoo. When Taiwan became Japan’s first colony in 1895, it became a testing ground for these imported ideals. In cities like Taipei and Hsinchu, the colonial government began constructing zoos that borrowed heavily from European precedents, blending German spatial logic with Japanese imperial ambition.

Decades later—and more than 5,600 miles from Hamburg—Hsinchu Zoo in colonial Taiwan quietly embodied the latest thinking in zoo design. Under Japanese rule, Taiwan became a proving ground for imported visions of modernity. Urban planning, architecture, and public institutions were developed in close step with contemporary trends in Europe, and the zoo was no exception.

At Hsinchu, visitors encountered not outdated colonial leftovers, but the cutting edge of early 20th-century zoological thought. The sloped enclosures, tiered rockwork, and lack of cages echoed the very principles first introduced at Tierpark Hagenbeck.

To this day, nearly every zoo around the world bears the imprint of Hagenbeck’s revolution. Every artificial rock backdrop, every moat or pool that separates animals from visitors—all of it can be traced back to the spatial logic first introduced at Tierpark Hagenbeck.

The revolution he sparked was undoubtedly one of the most significant leaps in the history of zoos. It overturned the very way people understood what a zoo could be. Of course, Hagenbeck’s approach was not without flaws—his vision prioritized spectacle over welfare. And yet, his radical ideas and bold experiments became the foundation of modern zoo design, guiding the field into a new century.

“I want to display live animals in nature, from the best possible angle.”

That simple dream, once uttered by Hagenbeck, has since crossed time and continents. It became a compass for generations of zoo professionals—and more than that, it quietly reshaped how millions of people around the world imagine what a zoo could, and should, be.

“African Panorama” today. (Source: Awesok / CC BY-SA 4.0)